What Is the Fjord Trail?

Scenic Hudson and their subsidiary, Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail (HHFT), want to build a major tourist attraction they say will be “the epicenter of tourism in the Hudson Valley” and have “national prominence.”

Stretching 7.5 miles from the Metro-North train station in Cold Spring to Long Dock Park in Beacon, the Fjord Trail would lead to years of heavy construction, degrade the environment, despoil the landscape, worsen traffic, bring an unmanageable number of tourists, and strain resources in the historic village of Cold Spring.

Table of Contents

1. Environmental damage caused by heavy construction

HHFT is planning for construction of the Fjord Trail to proceed in four stages:

At Breakneck Ridge, the first stage (HHFT refers to this as the “Breakneck Connector and Bridge”), four barges (some as long as a 747 airplane) would be docked and piled into the riverbed for two or more years. Vegetation would be ripped from the shoreline and turbidity curtains would be suspended in the river to trap increased sedimentation from erosion (Joint Application Form, 2023). Bedrock would be drilled to lay footers for a bridge spanning the Metro-North tracks. Heavy trucks would require regular access to the construction site from Route 9D, leading to increases in noise pollution, light pollution, and air pollution.

Following Breakneck Ridge, HHFT would proceed with similar construction along the shoreline (HHFT refers to this as the “Shoreline Trail”) from Dockside Park to Little Stony Point, from Little Stony Point to Breakneck Ridge, and from Breakneck Ridge to Long Dock Park. Within Hudson Highlands State Park, HHFT would have to cut down trees to build new and expanded parking lots and clear-cut a path between 10 and 14 feet wide for the Fjord Trail sections that go through the woods.

HHFT projects that building “the Fjord Trail and [Breakneck Connector and Bridge] … would result in about 55.6 acres of habitat disturbance” (DGEIS Ch. VI-5).

Construction impacts the environment, there is no way around it. Construction causes both air and water pollution and permanently alters the natural landscape. The removal of trees along the Hudson River shoreline will cause habitat loss and fragment ecosystems, pushing already threatened and endangered species (there are nine protected species—including sturgeon, birds, snakes, and lizards—that call this habitat home) further towards extinction.

In March 2025, crews began cutting trees and clearing ground cover on the west side of Route 9D at Breakneck Ridge. This phase of the Fjord Trail, which HHFT calls the Breakneck Connector and Bridge, was segmented from the broader environmental review process of the Fjord Trail under SEQR. The Breakneck Connector and Bridge includes building new parallel parking areas, parking lots, maintenance buildings, bathrooms, and a bridge spanning the Metro-North tracks at Breakneck Ridge. All told, HHFT expects building the Fjord Trail will result in 55.6 acres of habitat disturbance. The current work at Breakneck Ridge is just the beginning.

2. Scarring the shoreline with concrete and infill

Approximately 1.5 miles of the boardwalk and pathway that HHFT is proposing would run immediately parallel to Metro-North tracks and would be located mostly on MTA property and/or directly in the Hudson River. The southern portion of the shoreline boardwalk would run parallel to the train tracks from Dockside Park to Little Stony Point, and another section would run from Little Stony Point to Breakneck Ridge, which would culminate at the base of Breakneck Ridge with a large concrete platform infilled into the river. Building the concrete boardwalk would require driving approximately 284 pilings into the Hudson River shoreline between Dockside and Little Stony Point alone (DGEIS Ch. II-12). HHFT acknowledges, “Vegetation within the existing rip rap would largely be cleared, with some trees preserved where possible” (DGEIS Ch. II-8). Additionally, Figure II-2.C of the DGEIS shows that a 50-foot-wide corridor on the north side of Little Stony Point, an 18-foot-wide corridor in the area just beyond the footbridge at Little Stony Point, and a 12-foot-wide corridor on the south side of Little Stony Point would need to be cleared of vegetation to accommodate machinery for the construction of Fjord Trail South.

The shoreline boardwalk that HHFT is planning to build on the stretch of land from Dockside to Little Stony Point, shown above, would require construction of an elevated boardwalk with 284 pilings driven into the shoreline. Construction of this section alone is expected to last six years. The boardwalk itself would be elevated four to five feet above the Metro-North tracks and have an eight to twelve-foot-tall security fence on the side facing the tracks. By necessity of the elevated structure, natural vegetation and shaded areas would be limited.

MTA requires the shoreline boardwalk to be at least 25 feet from the tracks and have an eight to twelve-foot-tall security fence separating the trail from the tracks (DGEIS Ch. IV.G-6). These siting requirements would force the structure to be built in the water. HHFT has indicated that the shoreline trail would be constructed with a combination of pilings driven into the shoreline and riverbed to build an elevated structure and filled directly into the river to build a berm (see Arup, “Shoreline Trail Constructability”). That’s a major problem for HHFT because regulatory agencies don't want structures for non-water-dependent uses in or over navigable waters.

3. Over-tourism isn’t pleasant for tourists, either

According to calculations released in June 2024 by Philipstown’s members of the HHFT Visitation Data Committee, the Fjord Trail may attract up to 1.1 million visitors annually—roughly double the visitation number HHFT initially projected.

Cold Spring’s residential sidewalks are unequipped to accommodate the sheer volume of crowds that HHFT is envisioning and, indeed, hoping to attract. In 2021, HHFT arrived at this conclusion themselves when they ruled against routing the Fjord Trail along sidewalks on Main Street and Fair Street in the upper village. On both streets, they wrote, trees would need to be cut and sidewalks would need to be expanded to accommodate crowds, which would require “necessary easements” and “acquisitions of private property” (Alternative Alignments Analysis, 2022; 17).

Under HHFT’s current plan, crowding on Market Street, Main Street, and West Street in the lower village will likely be much worse than if HHFT had routed the Fjord Trail down Fair Street. HHFT envisions that the boardwalk from Dockside to Little Stony Point will “likely be a destination unto itself given the potential for water access, views, and direct connectivity to popular local attractions” (Alternative Alignments Analysis, 2022; 18). Think current crowding—but worse.

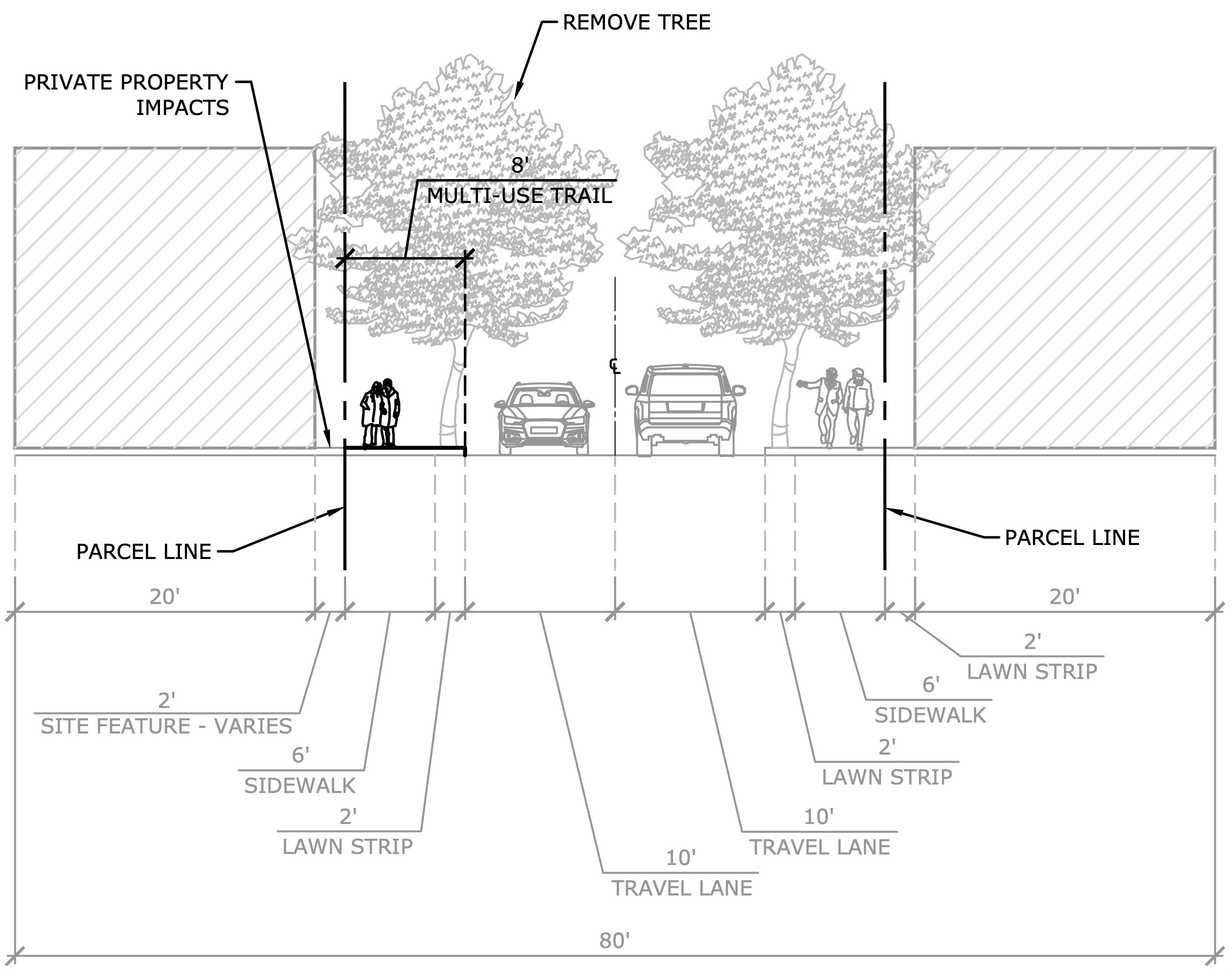

This drawing from HHFT shows the tree removal and “private property impacts” that HHFT says would have been necessary to expand sidewalks to accommodate crowding from routing the Fjord Trail along Fair Street. HHFT’s current plans call for routing the Fjord Trail along sidewalks in the lower village of Cold Spring that are just as narrow as the sidewalk on Fair Street. Source: Alternative Alignments Analysis, 2022; 65.

4. The Fjord Trail will not provide the open space you seek

HHFT envisions that the 1.5-mile shoreline boardwalk—which would be between ten and fourteen feet wide and have an eight-foot-tall barrier fence on the side next to Metro-North train tracks—would be open to people walking, hiking, running, rollerblading, walking dogs, biking, using wheelchairs, pushing scooters, fishing, landing kayaks, and wading into the river. Imagine Walkway Over the Hudson, but almost 60 percent narrower. Imagine the causeway on the Brooklyn Bridge, but with people casting fishing lines next to your head. Imagine the caged bike lane on the George Washington Bridge, but with people toweling off in the fast lane. HHFT often boasts that the shoreline trail will be universally accessible, but this is an over-promise. The trail use that HHFT is currently advertising will be dangerous for all users alike.

The boardwalk on the Fjord Trail would be almost 60 percent narrower than Walkway Over the Hudson, shown above. Image credit: Scenic Hudson.

5. Climate change and flooding

Scenic Hudson, the parent organization of HHFT, notes that the Hudson River’s water levels are expected to rise six or more feet by the end of this century due to climate change, and possibly an additional six feet during the next century. Six feet of sea level rise would permanently flood large areas of the Fjord Trail, including:

The lower village of Cold Spring

Dockside Park

The shoreline sections of Metro-North tracks from Dockside Park to Breakneck Ridge

The north side of Little Stony Point

The approach to Undercliff at Breakneck Ridge

The Breakneck Ridge train station and surrounding area

Consequentially, Scenic Hudson’s sea level rise modeling takes into consideration only sea level rise, not extreme weather events. Add extreme weather to the equation and the extent of expected flooding becomes even more severe, as these reports from the Columbia Climate School demonstrate.

On Sunday, July 9, 2023, the Hudson Valley suffered catastrophic flooding from a severe rainstorm. That afternoon, Cold Spring received six inches of rain, and other communities throughout the Hudson Valley received even more rain. The above image shows the tunnel underpass in Cold Spring beneath that Metro-North train tracks, which on a typical Sunday afternoon would have been crowded with people.

Indeed, even now, at the relative onset of sea level rise, the effects of flooding from extreme weather events are being acutely felt in the Hudson Valley. Recent repeated flooding in the lower village of Cold Spring plainly demonstrates that flooding is a present threat, not a future threat. In the years and decades ahead, these threats will become increasingly pronounced as the effects of sea level rise and extreme weather compound one another. As Cold Spring mayor Kathleen Foley recently stated, “We are actively living with climate collapse. We have to talk about it openly, particularly as New York State is considering connecting our fragile waterfront to the Fjord Trail. . . . [We need to have] honest and serious conversations about our infrastructure needs at the waterfront and whether trail development makes sense in that part of the village.”

The above video shows flooding on West Street in the lower village of Cold Spring on January 13, 2024. The rain storm, which coincided with melting snowpack and high tide, flooded numerous low-lying areas along the river, leading to property damage in Cold Spring, the temporary suspension of Metro-North service between Garrison and Beacon, the temporary closure of Route 9D north of Philipstown, and damage to dozens of cars at the Beacon train station.

6. More parking spaces equal even more cars

Once the Fjord Trail is built, HHFT plans to make use of 148 municipal parking spaces in the Village of Cold Spring, 200 parking spaces at the Cold Spring Metro-North train station, 30 municipal parking spaces in the City of Beacon, 631 parking spaces at the Metro-North parking lot in Beacon, 789 parking spaces at parking lots operated by HHFT and Scenic Hudson (DGEIS “Appendix III/IV.L-6: Parking Supply Table”). HHFT plans to charge visitors to park at lots operated by HHFT and Scenic Hudson. Municipal parking in Cold Spring and Beacon would be subject to local parking restrictions set by the municipalities—in other words, either free or subject to a meter—and the Metro-North lots would provide free parking on weekends.

To this end, HHFT envisions that on weekends, when parking is free, the Metro-North parking lot in Beacon will serve as the “no-cost parking option for any visitors who are unwilling to pay the daily fee at HHFT’s parking lots,” with the same principle also applying to the Metro-North parking lot in Cold Spring.

HHFT anticipates that, once the Fjord Trail is fully open in 2033, HHFT will implement a demand-based parking fee structure, charging between $10 per car under the lowest price tier at non-peak hours and up to $35 per car under the highest price-tier during peak hours at HHFT-operated parking lots (HHFT, “Request for Proposals: Parking Lot and Shuttle System Operation,” Exhibit E).

HHFT’s plans for paid parking at HHFT-operated lots will limit access to only those who can afford it and draw more traffic into congested residential areas. More parking lots will lead to more cars, resulting in more noise pollution, air pollution and traffic both on Route 9D and throughout surrounding communities. Think peak season—but worse, and during more of the year.

Fjord Trail Parking Areas Proposed by Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail

With 75 percent of visitors to the Fjord Trail expected to arrive by car (DGEIS Ch. III.L-18), new and expanded paid parking lots will turbocharge parking demand and create financial incentives for visitors to seek out parking on municipal streets in Cold Spring and Beacon. HHFT’s visitor management plan will lead to more traffic, more crowding, and further strain municipal resources. Source: Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail: Draft Generic Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix III/IV.L-6: “Parking Supply Table”

7. Traffic will bottleneck on Route 9D

Route 9D is the only through road with access to the Fjord Trail, and it is also the primary access point for the parking lots that HHFT is planning to build. According to HHFT, 77.7 percent of surveyed visitors arriving at Breakneck Ridge arrive from the south, specifically the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, and HHFT expects 75 percent of visitors to the Fjord Trail to arrive by car (DGEIS Ch. III.L-18). HHFT is planning to build more parking to accommodate more cars. But our meandering two-lane roads are unequipped to accommodate the sheer volume of traffic that the Fjord Trail will bring to the region. The additional parking lots that HHFT wants to build along Route 9D will create bottlenecks, leading to backups.

Route 9D, shown in red above, is the only through road with access to the Fjord Trail.

Traffic is already an issue on Route 9D during peak tourist seasons, frequently backing up from the stoplight in Cold Spring to the Butterfield Condominiums, where it spills over into residential side streets. Traffic ruins experiences for visitors, complicates weekend routines for residents, and hampers response times for emergency police, fire, and ambulance services.

During peak visitor seasons, traffic on Route 9D frequently stretches from the traffic light in Cold Spring to Butterfield Condominiums, as shown above in October 2023—a back up of more than half a mile.

8. Traffic will overwhelm the Village of Cold Spring

The fees that HHFT plans to charge for parking will incentivize visitors to seek out alternative free parking on residential streets in Cold Spring and Philipstown and at the Metro-North parking lot in Cold Spring, which HHFT has indicated would function as the southern beginning and ending point for the Fjord Trail. HHFT has identified 148 municipal parking spaces in Cold Spring that would service the Fjord Trail (DGEIS App. III/IV.L-6).

Cold Spring’s one-way-in, one-way-out streets are unequipped to accommodate the massive influx of cars that the Fjord Trail is expected to bring to the region. HHFT’s parking plan will to lead to more cars, traffic, noise pollution, and air pollution in Cold Spring, as drivers circle village streets and the Metro-North parking lot in search of coveted free parking spots.

HHFT acknowledges that use of the Metro-North parking lot for the Fjord Trail and operation of shuttle buses throughout Cold Spring would cause “traffic on Main Street [to] increase.”

The Metro-North parking lot in Cold Spring routinely fills to capacity on peak weekends. Demand for free weekend parking on Village streets and at the Metro-North train station will cause more traffic, noise pollution, and emissions in Cold Spring.

9. Reckless financial planning and shoreline commercialization

HHFT currently has a reserve fund of approximately $3 million and, rather than raise additional money for an endowment, has indicated that they intend to fund operations through parking and shuttle bus fees. Additionally, HHFT’s contract with New York State allows it to sell advertising, concession stands, and corporate sponsorships anywhere on the Fjord Trail, which they say “might be important sources of funding for both development and operations” (Agreement between NYS OPRHP and HHFT, 2021; 12).

Although HHFT has so far refused to publish an expected annual operating budget for the Fjord Trail, the final budget is bound to be massive. Hudson River Park in New York City—a similarly sized park that runs adjacent to the Hudson River—offers a useful comparison. In their 2022–2023 fiscal year, Hudson River Park had an annual operating budget of $23,950,809. Of this total, Hudson River Park spent $7,114,781 on park maintenance; $3,348,354 on public safety and security; $1,540,646 on sanitation; $1,931,787 on utilities; and a staggering $6,688,904 on insurance (Approved Budget vs Audited Actuals, FY 2022-23; 2).

Absent a functional endowment, HHFT will be forced to maximize visitation and monetize visitor experiences, turning Philipstown into a staging ground for the Fjord Trail’s operations.

10. Higher taxes

Local taxpayers, directly or indirectly, will foot the bill for additional EMS, police, traffic control, trash collection, water, wear and tear to the village, and other unreimbursed costs. That’s because HHFT will only be responsible for maintenance and operational costs within the physical boundaries of the Fjord Trail, even as they draw more tourists to Cold Spring with a boardwalk attraction. Unfortunately, sales tax revenue won’t help either. That money is sent to Putnam County.

Cold Spring already struggles to manage the enormous amount of trash that is generated during the busy seasons, and HHFT plans to foot Cold Spring with the bill for the additional trash collection that will be required in the Village if the Fjord Trail is built.

The boardwalk sections of the Fjord Trail and the railroad overpass at Breakneck Ridge will have their own maintenance costs, which HHFT will likely hand off to New York State Parks following the end of construction. If this happens, even as HHFT generates revenue from their operation of the Fjord Trail, the underlying costs to maintain the Fjord Trail infrastructure—including the bridge at Breakneck, the pilings in the river, the concrete fill, the railings and fencing, the inevitable damage from flooding, among so many other capital expenses—will be passed on to New York State taxpayers.

11. Another trail is reachable from here

Protect the Highlands has long advocated for building a more modest trail that would be cheaper to build, easier to maintain, more climate resilient, remain in scale with its surroundings, and improve accessibility for residents, visitors, and people of all mobilities alike.

What might this look like? In short, a modest trail would stay on the ground and out of the river. It would improve safety and accessibility. It would respect our natural surroundings—the river, mountains, and wildlife that together make our region so special. It would acknowledge the spatial limitations of our 19th-century towns and the carrying capacities of our winding two-lane roads.

In fact, long before Scenic Hudson, HHFT, and their billionaire donor co-opted planning for the Fjord Trail and began trying to morph it into a “world class linear park,” residents of Philipstown had been working together to build a more modest trail. The original Fjord Trail traces its origins to a community-driven 2007 greenway grant feasibility study—a study that found in the contours of our region’s magnificent geography the beginnings of an at-grade trail that would improve recreation, safety, and accessibility. Philipstown needs infrastructure and we deserve better than the concrete monstrosity that Scenic Hudson and HHFT are trying to force upon us.

Read about the Upland Alternative proposed by Protect the Highlands

The Upland Alternative is designed to protect hikers, improve ADA accessibility, and promote sustainable levels of tourism.